BirdsCaribbean Community,

It is with great excitement that we welcome our new BirdsCaribbean Board of Directors to the organization, and to our community. As a reminder to our member base, an election was waived this year because all candidates ran unopposed. That being said, we are welcoming many new Directors to our Board, who bring unique talents and backgrounds, as well as representation from Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Cuba, and Grenada. We also welcome back several members of the previous Board, who are eager to help guide the transition and continue their hard work on behalf of BirdsCaribbean. Below you will meet this great team of new and returning faces, who are ready to help lead BirdsCaribbean into even more productive and successful years ahead.

President — Adrianne Tossas, Ph.D.

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Three terms on the BC Board of Directors (2003–2004, 2005–2006, and 2019–2020), co-founder and first coordinator of the Caribbean Endemic Bird Festival (2002–2005), current co-chair of the Mentorship Program.

Nationality: USA

Residence: Puerto Rico

Experience: Adrianne has taught biology at the university level since 2004, leading undergraduate students in avian ecology research and conservation work. Prior to teaching she worked with the Puerto Rican Ornithological Society (SOPI), implementing the Important Bird Areas program from BirdLife International in Puerto Rico. Adrianne is the author of the book Birds of Puerto Rico for Children, and regularly gives talks and contributes newspaper articles about conservation for the general public.

“As President of BirdsCaribbean I want to help the organization grow by promoting broader participation in current flagship programs and working groups, by recruiting a diverse and inclusive membership, and by strengthening partnerships with other organizations. I will also be working to make sure that the organization has the resources it needs to carry out its work. My goal is to continue moving BC forward as the leading ornithological and conservation organization in the region.”

Vice-President — Justin Proctor, M.Sc.

Vice-President — Justin Proctor, M.Sc.

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Vice-President (one term), Managing Editor of Journal of Caribbean Ornithology (4 years), and conference organizer.

Nationality: USA

Residence: Front Royal, Virginia

Experience: Justin has a long and geographically scattered background of working in the fields of science, conservation, and education, from interpretation with the National Park Service in Maine, to underwater research with lobsters and shellfish in the Bay of Fundy, to youth adventure tourism in St. Martin and Costa Rica. After several years as program coordinator for Cornell’s Swallows of the Americas Project, Justin has carved out a niche for himself working extensively with aerial insectivore species, specifically swallows and swifts, from northern Canada down through Argentina. He conducted his master’s work on the threatened and endemic Hispaniolan Golden Swallow, and he also conducted an extensive search for the (likely) extinct Jamaican Golden Swallow. His work both domestically and internationally has included roles with non-profits, the National Park Service, the public education system, and university research projects. He is passionate about connecting communities with their environments, and in doing so instilling a greater sense of local environmental stewardship.

“Continuing on as Vice-President of BirdsCaribbean, I want to focus on attracting new members to the organization (early career professionals and new researchers in the region), helping them network, and getting them involved and engaged with the myriad programs that are underway throughout the Caribbean. I also plan to continue developing the BC Mentorship Program, help secure long-term funding for the Journal of Caribbean Ornithology, and continue improving our biennial conference experience for the BirdsCaribbean community.”

Secretary — Emma Lewis

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Member since 2013 when she joined the Media Working Group (currently the Chair). Was a member of the Organizing Committee for the BirdsCaribbean International Conference in Jamaica, 2015. Writes and edits media releases, articles, and blog posts for the BC website.

Nationality: British

Residence: Permanent Resident of Jamaica

Experience: Emma worked in International Banking in London for eight years before moving to Jamaica in 1988. She has since worked as a Public Affairs Specialist in the U.S. Embassy of Jamaica (1995–2011), worked in publishing/retail bookselling in Jamaica (1988–1995), and is now a freelance online writer and blogger. She has hosted her own personal blog (“Petchary”) since 2010 that regularly reports on environmental and conservation issues in Jamaica and throughout the Caribbean. Emma also conducts media/social media training, in recent years for a European Union NGO project and for the Press Association of Jamaica.

“As Secretary, I would like to see BirdsCaribbean continue to steadily expand its advocacy for birds and their habitats in the Caribbean, design programs with greater outreach to ‘unattached youth’ (ages 16 to 30 years) in rural areas, establish relationships with the Caribbean private (corporate) sector and young entrepreneurs to help develop local green economies, support and publicize BC’s projects through sponsorships, and establish/strengthen and maintain mutually beneficial relationships with international organizations such as UNEP and IUCN.”

Treasurer — Nicholas Sorenson*

Treasurer — Nicholas Sorenson*

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Monthly donor since November 2016 and now officially joined as a BC member; is the son of two ornithologists*, has traveled to numerous Caribbean islands, and has spent a lifetime exploring nature.

Nationality: USA

Residence: Miami, Florida

Experience: Nicholas (Nick) has extensive experience in financial consulting, with project work including financial statement analysis, business valuation, capital budgeting, trend analysis & forecasting, and strategic planning. He has served on the Alumni Advisory Committee for the Boston University Student Managed Investment Fund, was a Business Associate for Wellington Management Company, and an Analyst for the Michel-Shaked Group. Nick is currently a founder and managing partner of Ventus Advisors, and the Business Operations Manager at Lovepop. Nick greatly values environmental conservation efforts, scientific research, and global sustainability.

“As Treasurer, my focus will be to help BirdsCaribbean align its operations with its strategic and business development plans, which together will chart out a clear path for the organization to grow and manage its primary sources of funds (e.g., CBT/tourism, monthly donors, HNW/corporate sponsors, grants, etc.). I’ve worked with a number of startups as an advisor to help them develop customized financial/data-driven solutions, create external presentations, raise funding from investors, and optimize all aspects of the business. I’m excited about the possibilities for BirdsCaribbean because of my familiarity with its valuable work.”

*I hereby formally acknowledge that I am the son of Lisa Sorenson, the current Executive Director of BirdsCaribbean, and that this immediate family connection could be perceived by others as a conflict (either internally or externally). Based on my review of BirdsCaribbean’s 306 Conflict of Interest Policy, it is my understanding that there are procedures and comprehensive safeguards in place to ensure that all decisions will be made objectively and in the best interest of the organization, its board, employees, members, partners, and beneficiaries. I pledge to ensure that all matters, in particular those involving financial considerations, will be handled with the highest level of honesty and integrity. Finally, I do not currently have (nor anticipate having) any employment engagements, consulting projects, or business interests that would create or lead to a conflict with BirdsCaribbean’s key objectives and long-term mission as a non-profit organization.

Director-At-Large — Maikel Cañizares Morera, M.Sc.

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Member of BirdsCaribbean since 2011, Chair of the Local Organizing Committee for the 21st BirdsCaribbean International Conference and the Caribbean Birding Trail Workshop held in Topes de Collantes, Cuba. 2017. Has also attended and been active at the 2001, 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2019 conferences.

Nationality: Cuban

Residence: Havana, Cuba

Experience: Maikel works at the Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática in Havana. He is a conservationist, researcher, and educator. He holds a master’s degree in both Systematic and Applied Zoology (Universidad de la Habana, 2003), and Managing and Leading Conservation Projects (Cambridge University, 2016). Maikel has considerable experience in Psittacids management, Caribbean bird ecology and conservation, and working with people from rural communities. He was President of the Cuban Zoology Society since 2014 until 2019 and was President of the Cuban Chapter of the Mesoamerican Society for Biology and Conservation since 2010 until 2017.

“As a Director-At-Large, I want to support cultural integration and scientific exchange among bird lovers from our Caribbean nations.”

Director-At-Large — Jacqueline Andre

Director-At-Large — Jacqueline Andre

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Member of BirdsCaribbean since 2013. Participated in three BC International Conferences, including Grenada, Jamaica, and Guadeloupe.

Nationality: Dominican

Residence: Dominica

Experience: Jacqueline (Jacquie) is a Forest Officer with the Forestry, Wildlife & Parks Division in Dominica and is currently the head of the National Parks Unit. She has an undergraduate degree in Natural Resource Recreation Management from Virginia Tech. Jacquie has been involved with bird education for several years as the Environmental Education Officer of the Forestry, Wildlife & Parks Division, and attended her first BirdsCaribbean conference in Grenada in 2013.

“As a Director-At-Large, I want to help foster more education programs that would in turn create much-needed awareness and bring a deeper appreciation for nature in the Caribbean.”

Director-At-Large — Terry L. Root, Ph.D.

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Past participant in two of BirdsCaribbean’s Cuba tours, and a monthly donor to BC.

Nationality: USA

Residence: Sarasota, Florida

Experience: Terry was a Professor at the University of Michigan for 14 years and then Stanford University for 15 years. She was a lead author of the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change 4th Assessment Report that in 2007 was co-awarded the Nobel Peace Prize with Vice President Al Gore. Terry was also a lead author for the 3rd Assessment Report (2001) and a review editor for the 5th Assessment Report (2014). She has served on the Board of Directors of three different conservation NGOs (Point Blue 2002–2012, National Audubon 2010–2019, and Defenders of Wildlife 2010–2014 & 2020–Present) and has been the Science Advisor to the Board of Directors of the American Wind and Wildlife Institute (AWWI, 2012–2015 & 2019–Present). Additionally, Terry is currently a Science Adviser to National Audubon, Defenders of Wildlife, AWWI, and Climate Communication.

“I have worked my entire career on how climate disruption has influenced the biology of wild plants and animals, and how that influence has grave potential of facilitating the extinction of a quarter to half of the species on the planet. I believe my skills and expertise can help BirdsCaribbean attain their mission of raising awareness, promoting sound science and empowering local partners to build a region in the Caribbean where people appreciate, conserve and benefit from thriving bird populations and ecosystems.”

Journal of Caribbean Ornithology Editor-in-Chief — Joseph M. Wunderle, Jr., Ph.D.

Journal of Caribbean Ornithology Editor-in-Chief — Joseph M. Wunderle, Jr., Ph.D.

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Founding member of BirdsCaribbean in 1988, former Vice-President and President on the Board, and has contributed to the society’s first constitution & bylaws. Was co-organizer for the society’s conferences in Puerto Rico, Aruba, and Guadeloupe, and the Chair and organizer of the Founders Awards for best student presentations at four conferences. Has assisted with fund-raising and grant proposal writing to support workshops and regional conferences, participated as a presenter or a chair/organizer for workshops/special sessions at all conferences, and has served as a reviewer on the editorial board of Journal of Caribbean Ornithology since its beginning in 1988.

Nationality: USA

Residence: Puerto Rico and Georgia, USA

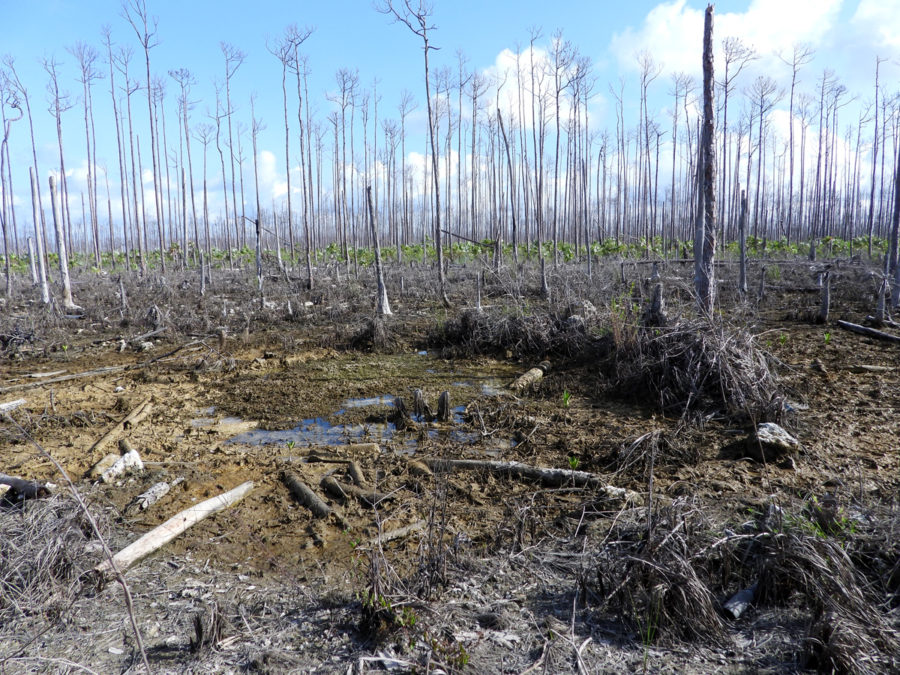

Experience: Joseph (Joe) did his dissertation research on the genetics, behavior, and ecology of the Bananaquit on the island of Grenada, W.I., where he lived for six years and taught in the Canadian Junior College for Marine Biology in the nearby Grenadines. Prior to moving to Puerto Rico, he taught and conducted research with the Organization for Tropical Studies in Costa Rica as well as at North Carolina State University. He was a professor in the Dept. of Biology, Univ. of Puerto Rico in Cayey for eight years before joining the U.S. Forest Service’s International Institute of Tropical Forestry in 1988, from which he recently retired after 30 years as a Wildlife Team Leader & Research Wildlife Biologist. He still maintains his ties with the University of Puerto Rico as an adjunct professor where he advises and teaches graduate students in ecology and ornithology. An underlying theme of his research is disturbance ecology, an understanding of which has facilitated his efforts to identify conservation prescriptions for bird populations threatened by disturbance from hurricanes, droughts, agriculture, and selective logging. He has authored or co-authored over 100 publications mostly based on his research on avian ecology and conservation biology, which he conducted throughout the Caribbean and Bahamas as well as in Central America and Brazil. In an effort to build local research and conservation capacity in the Caribbean and elsewhere, he has involved students and recent graduates from the region in his field research.

“I plan to continue to help strengthen BirdsCaribbean’s programs in education, outreach, advocacy, and transfer of scientific information related to avian conservation and ornithology in an effort to build local capacity to conduct research and foster conservation for Caribbean birds. Specifically, as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Caribbean Ornithology, I wish to build on the efforts of Jim Wiley and subsequent editors and their staff to increase the visibility and utility of the journal; to encourage and foster publication by Caribbean nationals; and to ensure the sustainability of JCO as an open access journal. JCO has an important role to play by facilitating communication among ornithologists, naturalists, and conservationists working in the region and by serving as a repository for studies of Caribbean endemic bird species and other species of conservation concern.”

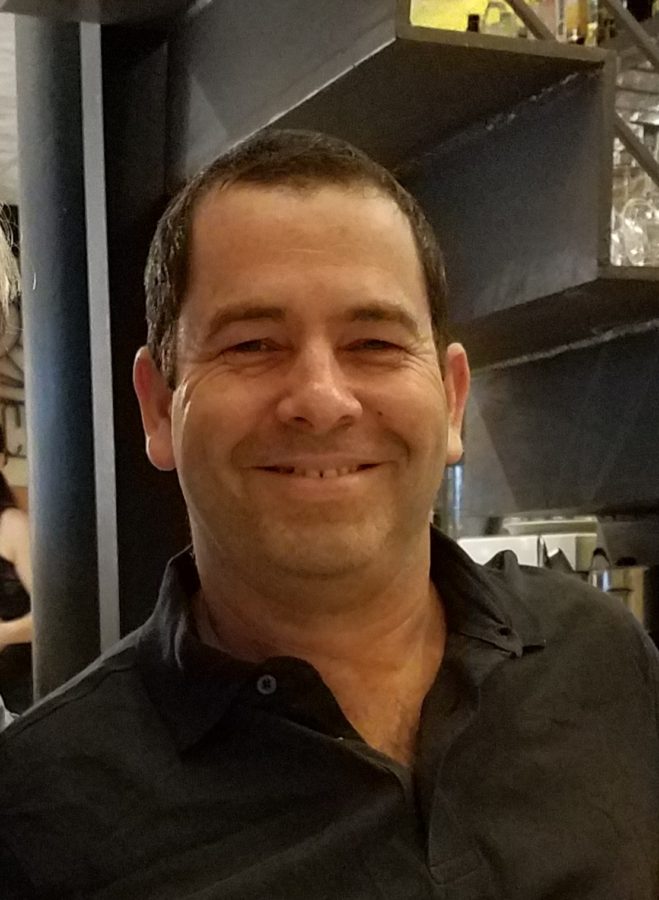

Past-President — Andrew Dobson

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Member since 2001, President of the Board 2005–2008 and 2017–2020, and led BirdsCaribbean tours to Cuba in 2019 and 2020.

Nationality: British

Residence: Cambridge, UK

Experience: Andrew was educated in the UK and has a B.A. in Economics (University of East Anglia), Post-Graduate Certificate in Education (Bristol University) and M.B.A. (Educational Management) University of Leicester. Andrew taught in Bermuda for over 28 years. He served on the executive of the Bermuda Audubon Society 1990–2018 including many terms as President. He produced the Society’s newsletter during that period and developed their website. He organized birdwatching courses, field trips, an annual bird camp, and coordinated the Caribbean Endemic Bird Festival and International Migratory Bird Day events in Bermuda. Since 1995 he has been a regional editor for the journal North American Birds. He attended his first BirdsCaribbean conference in Cuba in 2001 and has since served twice as the Society’s President. In 2002, his ‘Birdwatching Guide to Bermuda’ was published. He has co-authored articles on Bermuda’s IBAs and Bermuda’s birds. A keen photographer, his bird photos have appeared in many publications. He is a Life Fellow of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and a BirdLife International Rare Bird Club member. In 2018 he received an honour from Queen Elizabeth II for his contribution to the protection of Bermuda’s natural environment and his work with the Audubon Society. Andrew recently retired from teaching and moved back to the UK with his family where he remains active in birding and conservation action.

“I am honored to be part of an amazingly dedicated team committed to supporting such important bird conservation work in the Caribbean region. The Society reaches thousands of people in the region with its educational programs. I am proud of the response that BirdsCaribbean has given to island communities in the aftermath of recent disastrous hurricanes, especially the resources supplied quickly to feed starving bird populations. In an unprecedented period of climate change, I look forward to being part of a team working with local communities to create a better environment for both people and birds.”

Executive Director — Lisa Sorenson, Ph.D.

Executive Director — Lisa Sorenson, Ph.D.

Previous or current links with BirdsCaribbean: Member since 1996, Project Coordinator, WIWD and Wetlands Conservation Project 1997 to 2016, former Vice President and President of the Board, Executive Director 2013 to present.

Nationality: USA

Residence: Natick, MA, USA

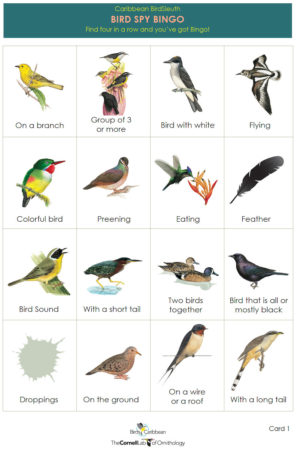

Experience: Lisa has a B.Sc. is in Wildlife, Fisheries, and Conservation Biology from the University of California, Davis, and a Ph.D. in Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior from the University of Minnesota. She has been working in the Caribbean for over 30 years and has expertise in waterbird and wetland ecology and conservation, climate change, conservation education, and surveying and monitoring techniques. Lisa raises funds for and oversees BirdsCaribbean’s various capacity building programs, such as the West Indian Whistling-Ducks and Wetlands Conservation Project, Caribbean Waterbird Census, BirdSleuth Caribbean, Caribbean Birding Trail Program, and bird festivals. She also works closely with our partners throughout the region, mentors students and young wildlife professionals, develops materials, and facilitates training workshops. Lisa became interested in Caribbean bird conservation through her PhD research on the breeding ecology and behavior of White-cheeked Pintails in the Bahamas and climate change impacts on wetlands and birds. She is passionate about her work and inspired by all the great work that our partners are doing to raise awareness and make a difference to help conserve the Caribbean’s amazing birds and biodiversity.

“Continuing as Executive Director, I want to grow and expand on all of our great programs in the region to conserve birds and nature. I believe that raising awareness and encouraging local citizens to know and appreciate birds, as well as get involved in science, monitoring, and conservation is vital to ensuring the long-term survival of the region’s incredible bird life. My priority is to continue building the capacity of our amazing local partners to carry out the fantastic work they do with their communities. We will build on our successes and strengths and grow the network of people that love birds and understand the value of local habitats for wildlife, sustainable livelihoods, ecosystem services, and ultimately, human health. I am honored to be part of an outstanding team that cares deeply about our mission and gives generously of their time and expertise. And I am thankful beyond words for our many partners, members, and supporters who believe in us and support our work in myriad ways.”

Director-At-Large — Jacqueline Andre

Director-At-Large — Jacqueline Andre