In 2022 BirdsCaribbean ran its first Caribbean Bird Banding workshop in the Bahamas. Get a first-hand account of the highlights of this workshop from Cuban participant Daniela Ventura. Want to know what a ‘Molt Nerd’ is? Read on to find out!

No, surely not! Not in my wildest dreams would I have imagined that in 2022 I was going to have the good fortune to visit not one, but two Caribbean other islands. As if that wasn’t unbelievable enough, the trips were scheduled with less than a month apart. But that’s exactly how things went: from learning to monitor landbirds using PROALAS point counts in the rainforest of the Dominican Republic’s misty mountains, I moved to the sunny beaches of Nassau in The Bahamas.

No need to tell you that birds were again the main driver and motivation. This time, I would receive training on banding techniques during the first Caribbean Bird Banding Workshop organized by BirdsCaribbean. The Retreat Garden of the Bahamas National Trust was our training oasis from 8 to 12 March.

Jewelry for birds?

Putting bracelets on birds? Have ornithologists gone mad? No, ornithologists are not crazy; and we do this for very specific and important reasons. It’s not about bird fashion either, though for me they look pretty fashionable.

Scientific banding has been a powerful tool for assessing bird populations for centuries. Nonetheless, I must admit that the first time I heard about banding I also was a bit lost. That happened at the 2017 BirdsCaribbean conference in Cuba. I was a sophomore student of Biology during the first and largest scientific event so far in my career. My mind was swirling! I wanted to absorb everything.

One day I entered the conference room and met Alina Pérez. She was giving a talk about her project monitoring migration in the Guanahacabibes Peninsula. I was amazed that such fabulous research was done in Cuba. At that time, I only knew they captured birds with mist nets, put tiny metal rings on their legs and let them go unharmed afterwards. I could not think of anything but the privilege it must be to hold a bird in your hand – and that I wanted to have that experience. After the conference I looked for Alina, introduced myself as an eager and inexperienced bird enthusiast, and told her I would love to volunteer with her project and learn from her. Alina gave me the warmest of her smiles and said “yes” right away.

I cannot thank Alina enough for the mentorship I received. Not only did she give me the opportunity to start learning the skills required to band birds safely and for scientific purposes, but she taught me so much more. During the three seasons I have spent volunteering on her project I still haven’t got used to the wonder of holding a bird in my hands. Most importantly, though, I discovered my obsession. Soon, I knew that I wanted to become a trained bander and to design research that incorporated this technique.

And so it was that, five years after the conference that changed my life, I was in a plane heading to Nassau, with my banding mentor sitting by my side, ready to walk the next steps of my path to become a certified bander. As I expected, the reality would surpass my expectations by far.

Breaking the bias

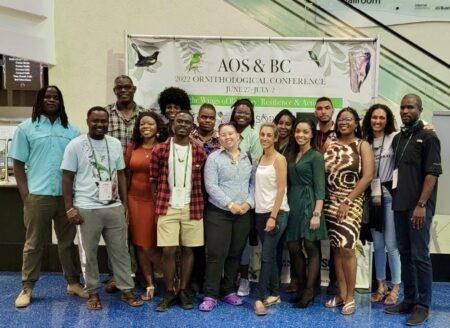

The first day of the workshop coincided with the celebrations of International Women’s Day. We had plenty of reasons to be joyful. This year’s theme, Break the Bias, highlighted the importance of addressing how our own social and cultural biases influence gender inequalities. The conservation industry in particular has a long history of being mainly male-driven. BirdsCaribbean is proudly breaking the bias as an organization led and carried by strong, committed, enthusiastic, and proficient women in science.

The main workshop organizers and trainers were women: Maya Wilson, Holly Garrod, and Claire Stuyck. Besides, among the participants we had the pleasure of having Anne Haynes-Sutton, one of the most influential conservationists in the Caribbean for her work with seabirds, and one of the pioneers of bird banding in the region. Nearly half of the attendees were also female, many of them young but already with important leadership positions and success stories in conservation to share. Alina Pérez, Adrianne Tossas, Shana Challenger, Zoya Buckmire, Johnella Bradshaw, and Giselle Deane were there to prove that women’s contribution to science and conservation should not be neglected and overlooked anymore.

Eating apples, admiring doves, and tying knots on Day One

Sessions were held at The Retreat Garden, a former private botanical garden and currently a National Park managed by The Bahamas National Trust. The park’s staff are world-class event organizers. They took good care of us by having a steady supply of coffee and snacks. This helped us to keep focus during the intense classroom and field sessions. If it wasn’t for the apples, I wouldn’t have made it! I must acknowledge that I have a serious addiction to apples and I was nicknamed the “Apple Terror” by my Puerto Rican friends. They had no choice but to head first thing in the morning to the snacks table, to grab and put aside an apple if they wanted to have a chance of eating one – before I went to the table and magically made them disappear. Sorry, pals!

The first lesson hadn’t started yet and I already had a lifer to add to my list. A pair of Caribbean Doves, walking unaware of our presence around the classroom facilities made such a pleasant view. Aside from the Cuban endemics, they are the most beautiful doves I have ever seen.

I was lucky to get good views of other notable Bahamian birds, like the stunning male Bahama Woodstar, the Bahama Mockingbird, and of course the ubiquitous White-crowned Pigeon. Definitely, the doves were the dearest to my heart.

Activities began when the trainers, Claire Stuyck and John Alexander from Klamath Bird Observatory, Steve Albert from the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP), and Holly Garrod from BirdsCaribbean, greeted and welcomed us to the five-day intense banding schedule. They had barely finished introductions when we were already getting hands-on learning about setting up mist nets, security guidelines, and tying knots. Making knots can be fun as well as stressful, at least for a person like me who doesn’t have a good spatial memory. But it speaks highly of our instructors’ teaching skills that I soon forgot my insecurities and became immersed in tying knots – and even had a lot of fun!

Getting to know (and love) the Birder’s Bible

Lessons comprised a blend of field practice in the mornings and theory talks in the afternoon. These sessions covered the nitty-gritty of setting up an organized and well-planned banding table, with all the tools and the equipment properly set up to meet our needs. There were talks about the Bander’s Code of Ethics; bird and human safety at banding operations; the use of molt strategies to identify ages; education and public outreach; the use of banding for scientific research; and other related topics.

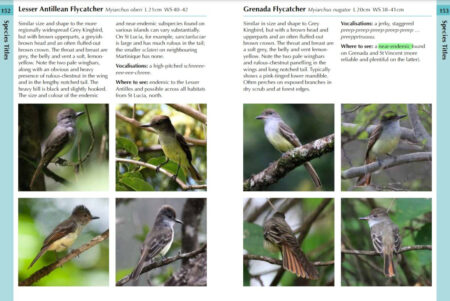

We split our time between banding demonstrations given by the experts Claire and Holly and conducting regular net runs. We had the luck of getting a closer look at resident birds like the Red-legged Thrush, La Sagra’s Flycatcher, Bananaquit, Thick-billed Vireo, Caribbean Doves, and Common Ground Doves, but also common winter migrants like Cape May Warblers, Black-and-White Warblers, and the American Redstart. Although the birds we captured were never enough to please us, everyone had their chance to learn how to extract birds safely out of the nets, and even handle and band them.

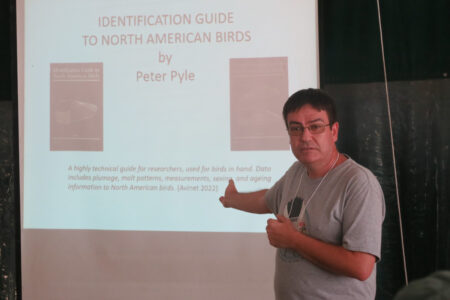

During the low-activity periods, time was well spent learning how to use the Bander’s Bible: The Identification Guide to North American Birds, known simply as “the Pyle”. Diving through the Pyle can be a hard pill to swallow for every amateur bander, but once you realize you can’t have a stronger ally at your banding operations, it becomes as dear to you as an old friend. Helping to make that connection even stronger was the fact that we knew the actual Pyle (yes, Pyle – the “Bander’s God”) knew about us, through his colleague from the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP), Steve Albert. We could feel his presence while we struggled to study molt patterns.

The molt obsession

Now – talking about molt. You can’t be a skilled bander without being a molt nerd. No doubt about that. In the beginning, we thought Holly was nuts when she started talking in a weird fashion about three-letter codes. Wolfe-Ryder-Pyle (WPR) codes for aging birds are another jaw-dropper for anyone new to the secrets of bird identification.

But of course, Holly is far from being nuts. She infused us with so much excitement while talking about molt strategies, that we all got enthusiastic about it. Pretty soon, our days became molt-centered – not only during the sessions, but at dinners, night gatherings at the hotel terrace, and even during the short but necessary break at the Orange Hill Beach. Everyone was truly proud at the end to be called a molt nerd.

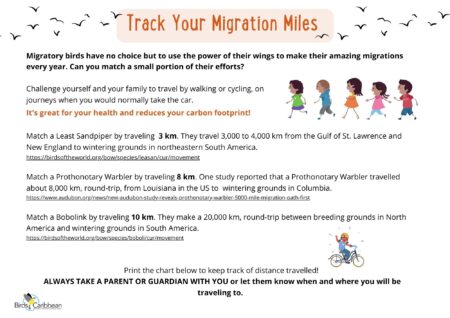

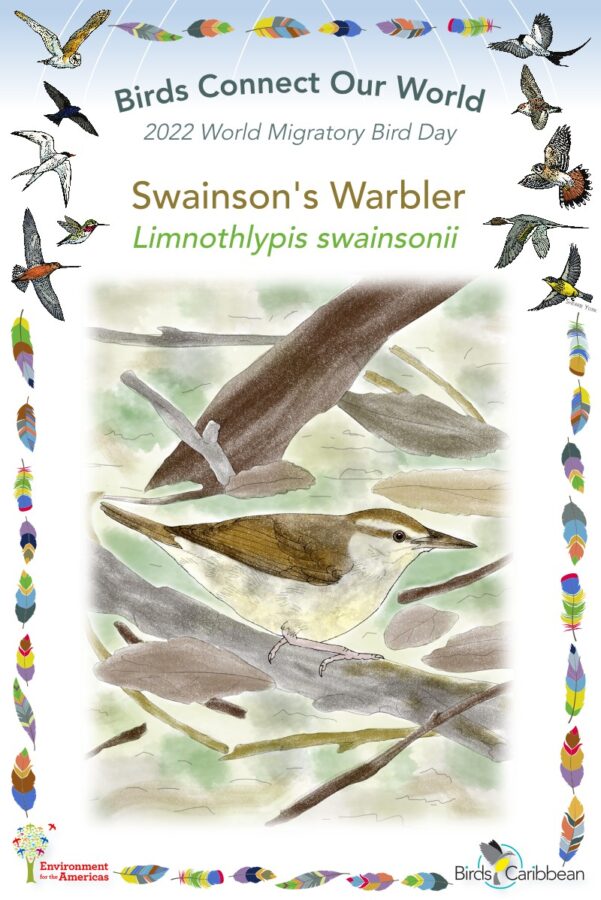

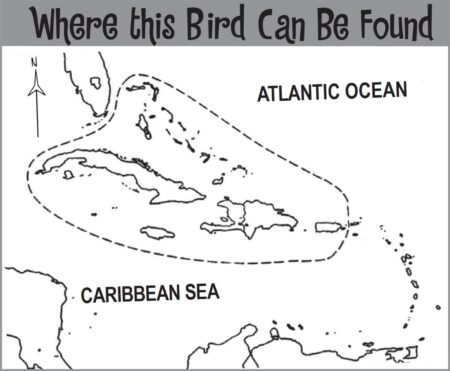

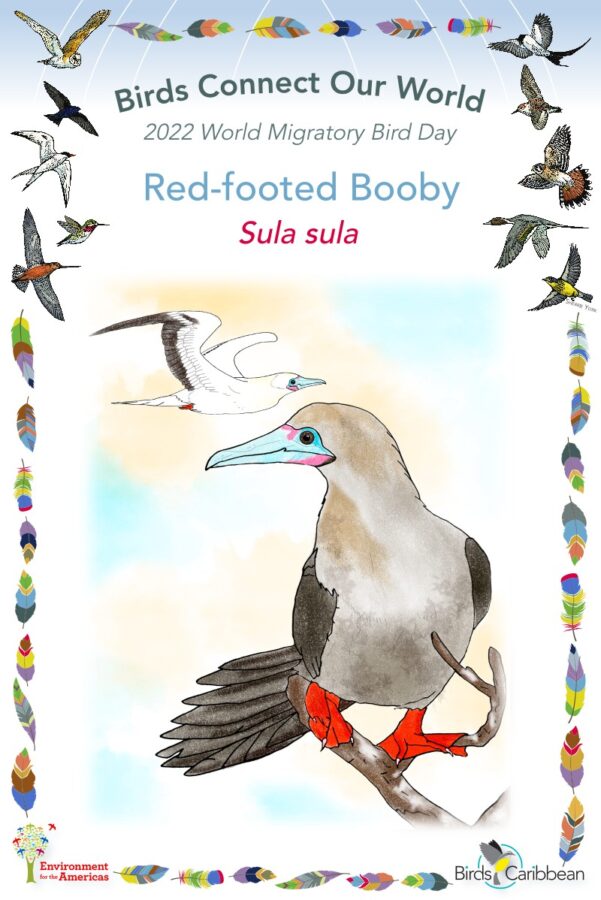

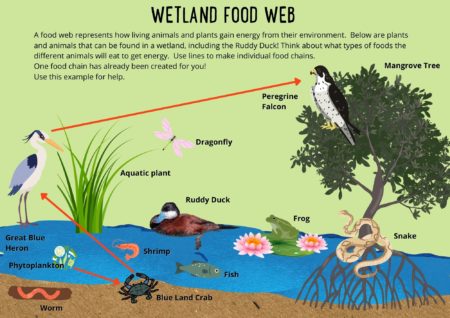

I know some of you may already be asking, what’s all this for? Are we actually helping birds by showing off our knowledge of fancy letters and metal and colored rings? In fact, we are helping both birds and humans alike. You probably already know that birds are powerful sentinels of change. Studying how their populations respond to and cope with changes to their habitats, and other threats such as climate change, are useful tools for planning conservation strategies. The Caribbean region is home to more than 700 species, 176 are unique to these islands. The region is also one of those places on Earth that are suffering from rapid transformation by humans.

Banding connects us with nature

But we have another problem, and it is that plenty of our birds’ natural history is still unknown, or at least inadequately studied. Banding can be a powerful tool to begin filling those gaps. Birds in the hand provide us with loads of data about population estimates and trends, survival rates, movement routes and timing, disease prevalence, overall health and condition, molt strategies, physiology, breeding phenology, and much more basic data for ornithological studies. Besides, holding banding demonstrations for the public offers a gateway that helps humans connect with nature, an invaluable resource to educate people about wildlife and conservation. I believe that holding a bird in the hand and then watching it fly away can have a profound effect on someone’s life. And I say this from my personal experience! Banding not only helped me discover my passions, but connected me with nature and conservation like nothing else had before.

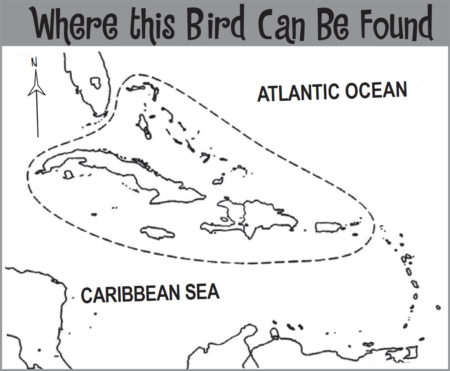

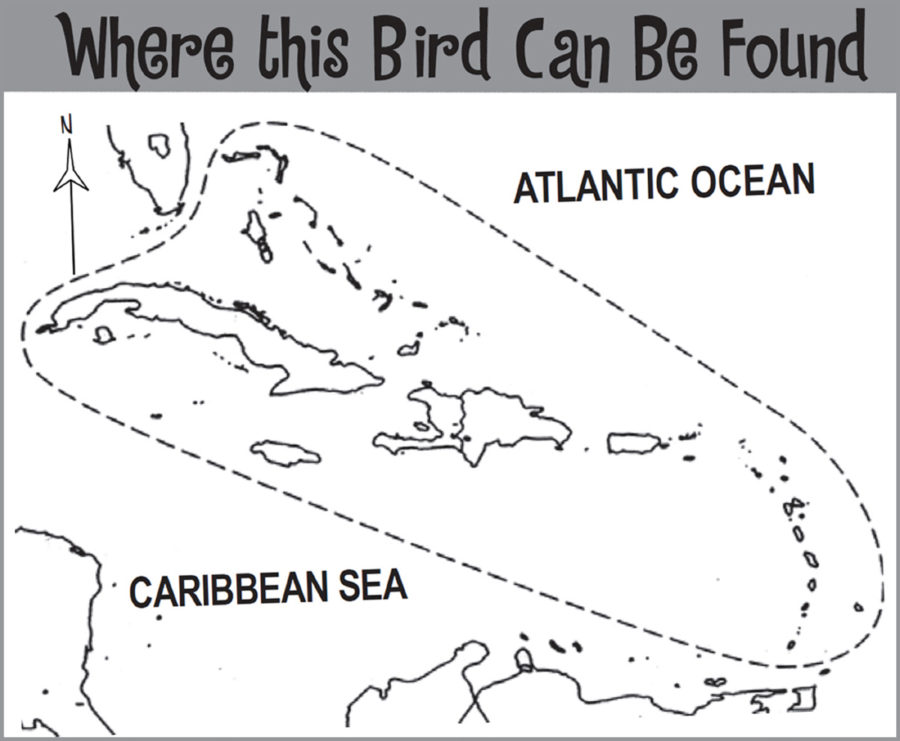

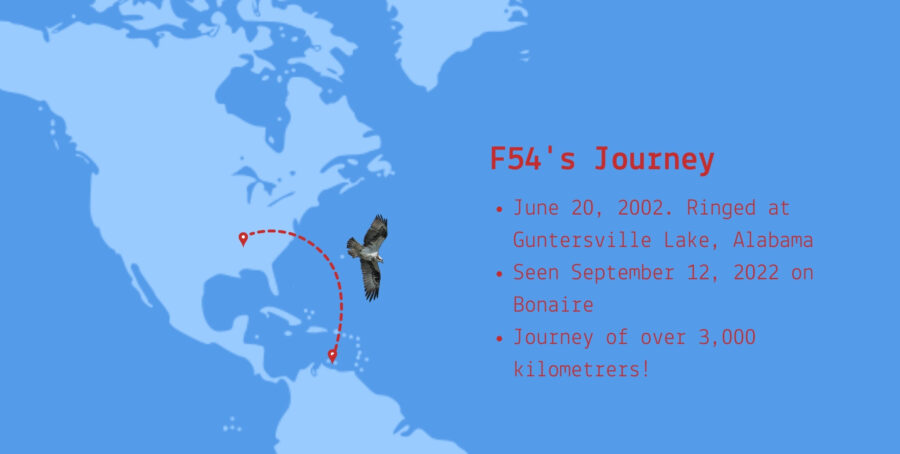

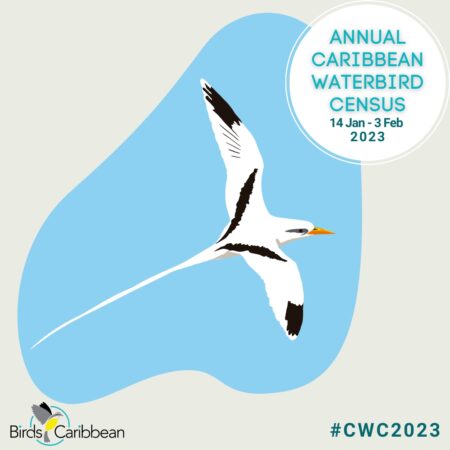

The whole aim of the workshop was to create a network of banders across the Caribbean that could employ a series of standardized protocols to begin answering questions still unaddressed about our birds’ basic ecology. The Caribbean is a crucial stopover and wintering area for many declining North American songbirds. For this reason, the workshop also included talks about the collaboration with the MoSI (Spanish for monitoring winter survival) program from IBP and the installation of MOTUS towers. By combining traditional banding and modern tracking technologies we could boost our understanding of the movements of Neotropical birds throughout the Caribbean region and beyond.

But the main step, besides establishing these connections, is training and capacity-building. We need to end the traditional model of “parachute science” and train our next Caribbean generation of banders and trainers. I am so happy that I can brag about being a friend of the brand-new certified North American Banding Council (NABC) trainer: Juan Carlos (JC) Fernández Ordóñez (yes, the humorous Latin team “influencer”). You can tell when JC is talking about bird stuff because it is the only time you will see him with a serious look on his face. And that does not necessarily mean he is not making jokes. JC has been banding for 25 years. He is knowledgeable about molt strategies and bird ID, not only of Neotropical but also European, African, and Asian species. Most importantly, he enjoys teaching and sharing all he knows with everybody. I am sure that with JC’s example and Holly’s magnetism, most of the participants left with the ingrained desire to continue mastering our banding skills and obtain NABC certification in the near future. That will help lift the banding movement in the Caribbean.

Real Bahamian hospitality!

“Welcome to The Bahamas” are not only the letters of a beautiful mural painted on Bay Street, but the greeting me and my friends received everywhere we went: at the hotel, restaurants, and from people driving a car late at night through the Downtown area. If nothing else, I will never forget from this trip the beautiful aquamarine, gold, and black Bahamian flags waving from almost every building, and the kind hospitality of the people. The Bahamians I met during that week were courteous, smiling, spicy-food lovers, and proud of their history and traditions. Our Bahamas National Trust colleague and fellow trainee, Giselle Dean’s organizational skills made the workshop run smoothly, and she would humbly say it was nothing. Bahamian Scott Johnson not only was kind enough to give us a ride every day from the hotel to The Retreat in his car, but entertained and amazed us with his tremendous knowledge of Bahamian natural history and culture. Chris Johnson was quiet much of the time, but surprised us by generously giving each of us a beautiful calendar with his bird photos! Many of the species are shared by Cuba and the Bahamas, so it is nice to flip through the months of the year and recollect the memories from the trip. Ancilleno Davis was a model host, giving us a tour around Downtown Nassau during the last day of our stay, and providing us with a taste of Bahamian arts, architecture, and history.

The “Plus/Delta” of it all

The “Plus/Delta” was a daily exercise for us at the end of the sessions. We highlighted the most significant aspect of the day for each of us and reflected on the areas where we needed more study or practice. It’s really difficult for me to decide on the overall Plus/Delta of my Bahamian experience. I have many of them. My Plus was the chance to bond with old and new friends; strengthen collaboration networks that will aid in my future professional development; improve my banding and molt ID skills; and widen my understanding and appreciation for other cultures.

And the Deltas? I also have plenty: I am determined to continue growing my expertise in all subjects regarding banding, bird ID, molt strategies, and overall bird ecology. A key step for achieving that goal is to become a certified NABC trainer. With this qualification, I do not want to only band and contribute to the understanding of Cuban resident species. I would also like to share and hopefully instill enthusiasm for these studies in the new generations of Cuban ornithologists. In the long run they will accomplish the visions we dreamed of on the beaches of the Bahamas. My biggest Delta is the hope that soon a large and powerful network of Caribbean banders will be the authors of a new round of success stories in regional bird conservation.

BirdsCaribbean Acknowledgments

This workshop would not have been possible without our dedicated trainers, enthusiastic participants, and funders, including the US Fish and Wildlife Service and US Forest Service and BirdsCaribbean generous donors and members.

![PIPLFW[YA]andFL[8P]CINSnorthbeach-Patrick-Leary Banded Piping Plovers](https://i0.wp.com/www.birdscaribbean.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/PIPLFWYAandFL8PCINSnorthbeach-Patrick-Leary.jpg?w=400&h=287&ssl=1)