Do not attempt, unless you are a ram goat (or a swallow), advises Justin Proctor.

From January 15th to February 12th and March 24th to 27th 2015, I surveyed the greater Cockpit Country region of Jamaica in search of the critically endangered Jamaican Golden Swallow (Tachycineta euchrysea euchrysea), accompanied by two other Cornell alumni: Seth Inman (La Paz Group) and John Zeiger (currently with the Aldo Leopold Foundation). One of the goals of the expedition was to spend considerable time censusing where the species had last been unequivocally observed in 1982, the Ram Goat Cave area of Barbecue Bottom.

However, in our efforts to research – and then ultimately find – Ram Goat Cave, we came across considerably more fiction than fact. The internet, multiple maps, a guide book or two, and many good-intentioned locals did a very noteworthy job of filling us up with misleading information and sending us down some dark and abrasive dead ends. For the record, we’re not complaining; the road less traveled in Jamaica always seemed to produce one of those classic “let’s not bring this up for a few years, but the grandkids will love it” stories. Yet in the end we did find Ram Goat Cave, and so here we aim to bring a little more clarification to a topic that few available resources seem to agree upon. We also begin to highlight the ornithological significance that the cave once may have had and where that finds us now.

To orient you, Cockpit Country is a roughly 1,160 km2 designation of land, known by its undulating karst limestone topography, situated in west-central Jamaica. On the east-central side of Cockpit Country, running roughly north to south between the towns of Kinloss and Albert Town, is a relatively flat valley floor known as Barbecue Bottom. The geological fault that created this aberration also left some stretches of the valley’s western flank lined with exposed cliff sides. It is about two-thirds of the way up one those vertical rock faces that the notorious Ram Goat Cave continues to endure. It is important to point out that an old dirt and gravel road (named Burnt Hill Road if approaching from the south and Barbecue Bottom Road if approaching from the north, sometimes referred to in older texts as the “carriage trail”), runs parallel to Barbecue Bottom. For the most part, the road has been etched into – and snakes along – the upper hillsides, offering the wayward traveler some incredible views along the way. There is a point along this road that positions an observer directly above Ram Goat Cave, although without prior knowledge of this it would be impossible to discern, as no view of the cave is afforded from any point along the road. Meanwhile, down within Barbecue Bottom, a now mostly overgrown “bridle trail” can be found meandering along the valley floor. It is from this trail that views of Ram Goat Cave are possible.

Much like us, the Jamaican Caves Organization (JCO) had quite the adventure tracking down this cave. But eventually, they did find it, and they do reveal its approximate location. However, even with the information from their account, one would still struggle to “find” Ram Goat Cave, because due to the location and orientation of the cave, as well as the density of the wet limestone forest that blankets the landscape below, it can only be viewed from certain vantage points, all of which are located down within Barbecue Bottom. Adding to that, Barbecue Bottom, despite once being populated and cleared for drying considerable quantities of coffee and pimento, is now, as the locals would say, “bush up.” Nature in the form of thick, almost impenetrable vegetation is reclaiming the land. However, this reforestation should be embraced during what are otherwise considered strained times for the Cockpit Country as it faces a plethora of threats, one of the most daunting being the growing interest in extracting bauxite from within the region.

To our knowledge, Ram Goat Cave has never been entered or explored, undoubtedly because the cave cannot be reached without considerable rappelling equipment and expertise. The JCO decided not to do so (in the Spring of 1998) after concluding the following about the cave’s morphology:

“Ramgoat Cave is situated roughly 50 m up a vertical cliff, and about the same below the road, and is a cave in name only. From what we could see, it appears to be a small shelter cave with an opening of about 5 m, that looks like it will extend no more than 10 m into the cliff. We did not, of course, attempt to enter it because there is no point. By looking at it from below, and by looking at the morphology of where it is found, it is obvious that it goes nowhere. It is a shelter cave that became famous many years ago because of its absolute inaccessibility. One would have to be a ‘ramgoat’ to reach it.”

Although the unassuming Ram Goat Cave may not offer much to a spelunker, it has long been a point of interest and reference for avid birders in Jamaica. The Broadsheets – a biannual journal (published by the Gosse Bird Club, which was renamed BirdLife Jamaica in 1998) that has been dedicated to compiling and disseminating ornithological observations in Jamaica since August of 1963 – is sprinkled with entries of bird observations occurring near the cave (all seeming to have been taken from the road above). Much to our interest, throughout the years entries into the Broadsheets note that some species of aerial insectivores, in particular Cave Swallows (Petrochelidon fulva), Golden Swallows, and Antillean Palm-swifts (Tachornis phoenicobia), were reliably seen flying, foraging and interacting in close proximity to the opening of Ram Goat Cave, which in turn raises the question of whether or not they may have been using the cave for the purpose of nesting and/or roosting. Take for example this excerpt from an entry by Audrey Downer and Robert Sutton from 1972 (Broadsheet 1972:12):

“On July 3rd 1972 we visited . . . a place called Ram Goat Cave on the Barbecue Bottom road where Golden Swallows have frequently been seen. Masses of Cave Swallow milled around, and with them several Golden Swallows. It had rained and puddles of water were on the road, which attracted the swallows. As the Golden Swallows swooped down to the puddles and then rose over our heads we could clearly see the white underparts. They then flew in the valley just below where we were standing and not more than 20 to 30 ft. away. In the overcast light the backs looked a bluish green and no yellow could be seen, but at that time of the year they could not be Tree or Bahama swallows.”

In fact, only ten years later, the last unequivocal sighting of the Jamaican Golden Swallow was seen in the greater vicinity of Ram Goat Cave, as is reported here by Audrey Downer (Broadsheet 1982:32):

“Is The Golden Swallow Declining?: In 1858 Osburn wrote to Gosse . . . describing Golden Swallows as appearing “in great numbers” over the canefields of Trelawny. Several years ago when Robert Sutton and I saw them at Ram Goat Cave there were only 5 or 6 seen at a time. No report has recently been recorded in the Broadsheet, but some visitors to the island in August this year [1982] reported seeing them on the Barbecue Bottom Road. In order to verify this report, a group of us headed by Robert Sutton went along this same road in the Cockpit Country on Sept. 11th, 1982. After stopping at Ram Goat Cave and Barbeque Bottom where we heard swallows but saw only Cave [Swallows] and [Antillean] Palm Swifts we stopped between the 15th and 14th mile-post at a spot overlooking the ruins of Stonehenge. Immediately below us was a grassy area with canefields in the distance. This looked like the spot described by the visitors, and sure enough Robert soon spotted a Golden Swallow circling with Cave Swallows … The visitors reported seeing 7 Golden Swallows, and we saw between 6 and 9 at a time. This is a far cry from the numbers reported by Osburn. Are they declining or are they more numerous after a rainy spell?”

There are other entries in the Broadsheets that also highlight the presence of multiple species of swifts and swallows foraging in the vicinity of Ram Goat Cave. Seth, John, and I have been diving into the implications of this in a manuscript that we are currently working on entitled, “Exploring the Plight of the Jamaican Golden Swallow,” which we hope to submit for review in the near future.

We opportunistically spent two evenings in mid-March of 2015 directly observing the cave from a distant vantage point down in Barbecue Bottom. This was a set of pilot observations in order to assess how more thorough documentation of avian activity in and around the cave could be implemented in the future. Our time observing the cave did not produce any positive sightings of aerial insectivores – or any other birds for that matter – making use of the cave. We do believe, however, that a regimented routine series of observations across a longer duration of the known breeding seasons for Jamaica’s aerial insectivores is warranted.

Beyond Ram Goat, Jamaica is incredibly abundant in caves. To our knowledge, the extent to which different bird species use – and potentially depend upon – these caves has yet to be studied. With so little known about the life histories of cliff/cave nesting species such as the White-collared Swift and Black Swift in Jamaica, it would seem fitting for ornithologists to combine forces with the Jamaican Caves Organization to better study and document these unique birds.

In the meantime, we encourage birders to responsibly visit the Burnt Hill / Barbecue Bottom Road region of Jamaica’s Cockpit Country (Cockpit Country Adventure Tours offers outstanding birding and caving tours in this area). We’ve found this to be one of the most serene wild areas left in Jamaica’s interior, and in hopes of keeping it that way, we suggest you walk the road by foot [a landslide has been effectively blocking the road in recent years anyhow, so you will be unable to make a through-trip by car]. As you go along, be sure to spend some time in the Ram Goat Cave area, exercise caution if you decide to descend down into Barbecue Bottom proper, and be sure to see how many of Jamaica’s endemic bird species you can check off along the way (28 out of 29 endemics have been found in the Cockpit Country!).

By Justin Proctor; Caribbean ornithologist, member of the JCO Editorial and Production team, and frequent contributor to our blog. Check out his article on the Golden Swallow in the Dominican Republic here.

Thank you to Ann Sutton, the Windsor Research Centre, and the Jamaica National Heritage Trust for contributing information to this article.

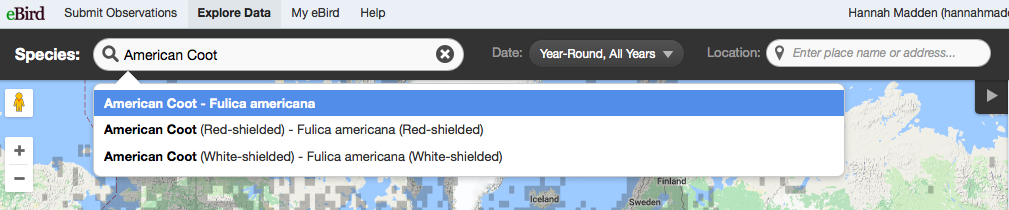

(Note: options may be considered “rare” in certain areas and will be hidden from the default list when you enter sightings.) All previous eBird Caribbean records of Caribbean Coot have now been listed under American Coot (White-shielded). Please use this option whenever you successfully identify a Caribbean-type coot and use the American Coot (Red-shielded) option for American-type coots. For more information

(Note: options may be considered “rare” in certain areas and will be hidden from the default list when you enter sightings.) All previous eBird Caribbean records of Caribbean Coot have now been listed under American Coot (White-shielded). Please use this option whenever you successfully identify a Caribbean-type coot and use the American Coot (Red-shielded) option for American-type coots. For more information

![An artist's rendition of the Semper's Warbler (Joseph Smit [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)](https://www.birdscaribbean.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Sempers-Warbler-LeucopezaSemperiSmit-450x300.jpg)