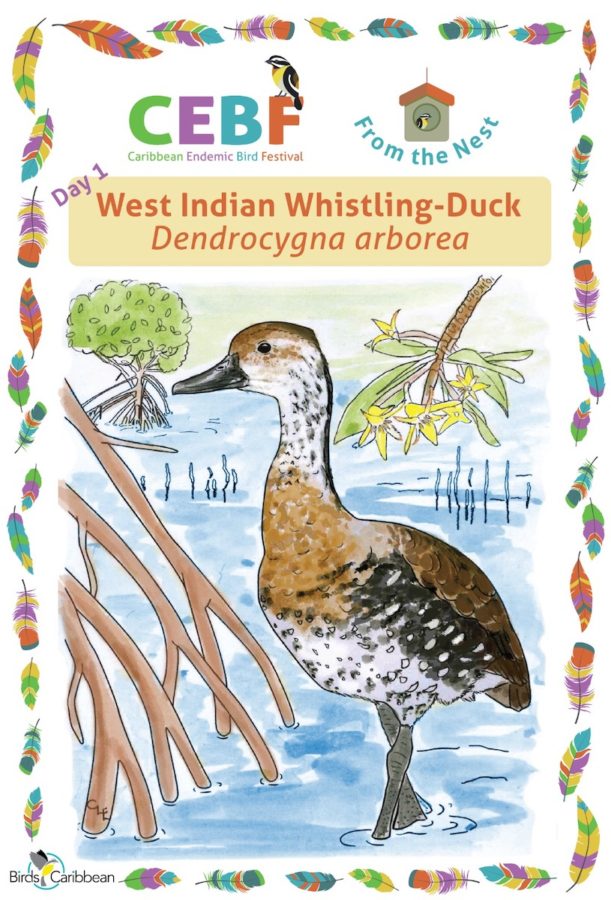

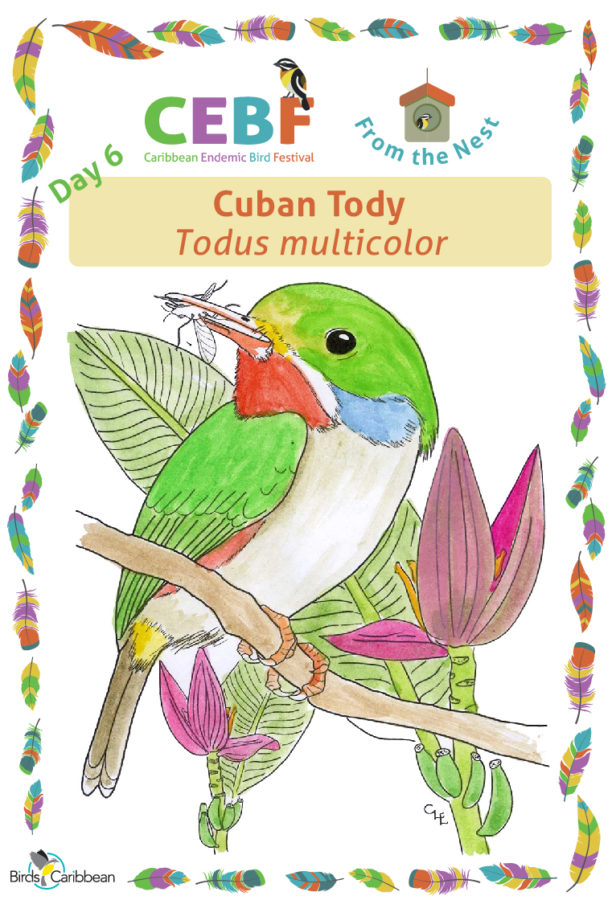

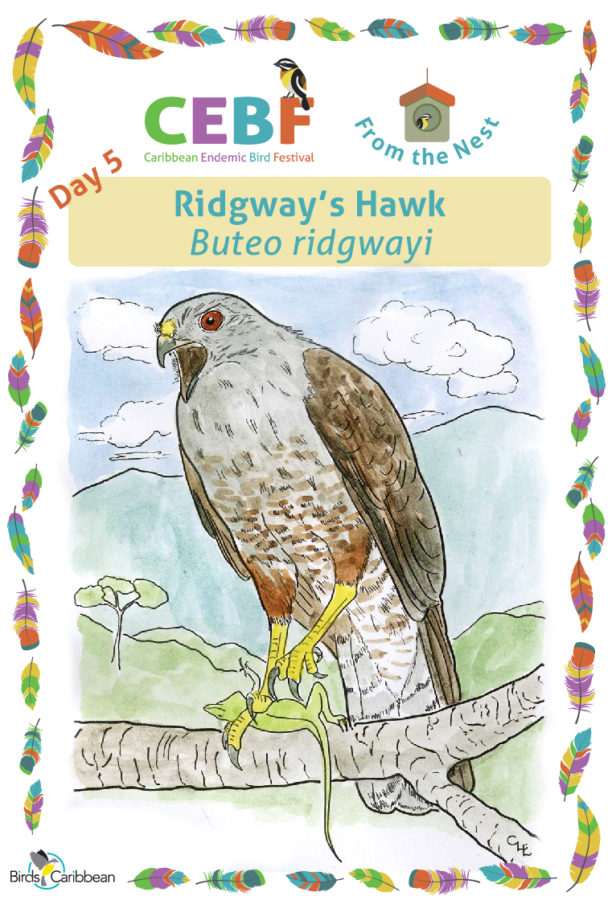

Celebrate the Caribbean Endemic Bird Festival (CEBF) with us in our virtual “From the Nest” edition! Have fun learning about a new endemic bird every day. We have colouring pages, puzzles, activities, and more. Download for free and enjoy nature with your family at home.

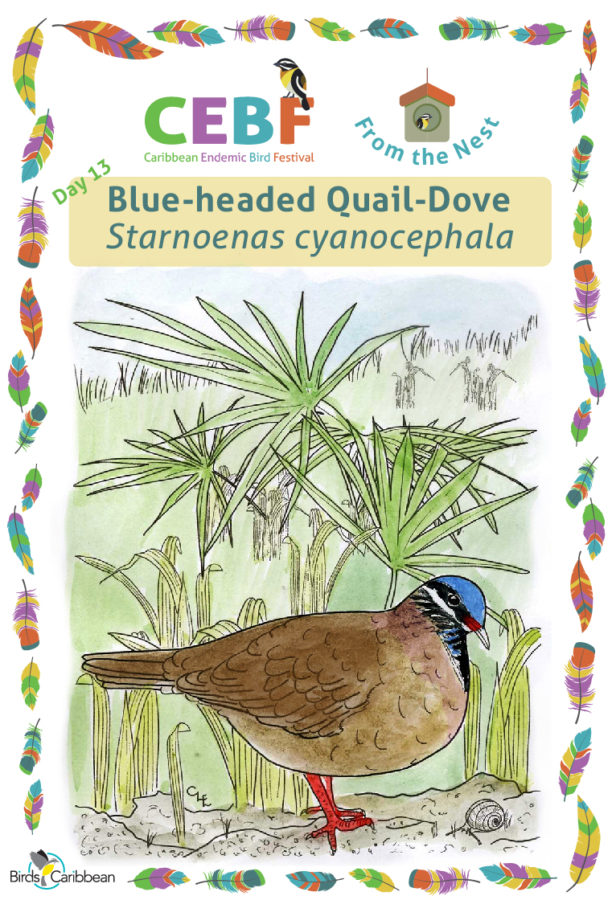

Endemic Bird of the Day: Blue-headed Quail-Dove

The Blue-headed Quail-Dove (Starnoenas cyanocephala) is the largest and most eye-catching of Cuba’s terrestrial doves. It has a cobalt blue crown, black eye line, white facial stripe, and black medallion on the throat and breast bordered by white. The sides of the throat have iridescent blue lines. The body is a cinnamon-brown color that blends in with dead leaves. This shy bird lives in dense forests where it walks constantly on the ground, often in pairs or small groups, searching for seeds, insects, snails, grubs, berries, and other fruits in the leaf litter.

The Blue-headed Quail-Dove (Starnoenas cyanocephala) is the largest and most eye-catching of Cuba’s terrestrial doves. It has a cobalt blue crown, black eye line, white facial stripe, and black medallion on the throat and breast bordered by white. The sides of the throat have iridescent blue lines. The body is a cinnamon-brown color that blends in with dead leaves. This shy bird lives in dense forests where it walks constantly on the ground, often in pairs or small groups, searching for seeds, insects, snails, grubs, berries, and other fruits in the leaf litter.

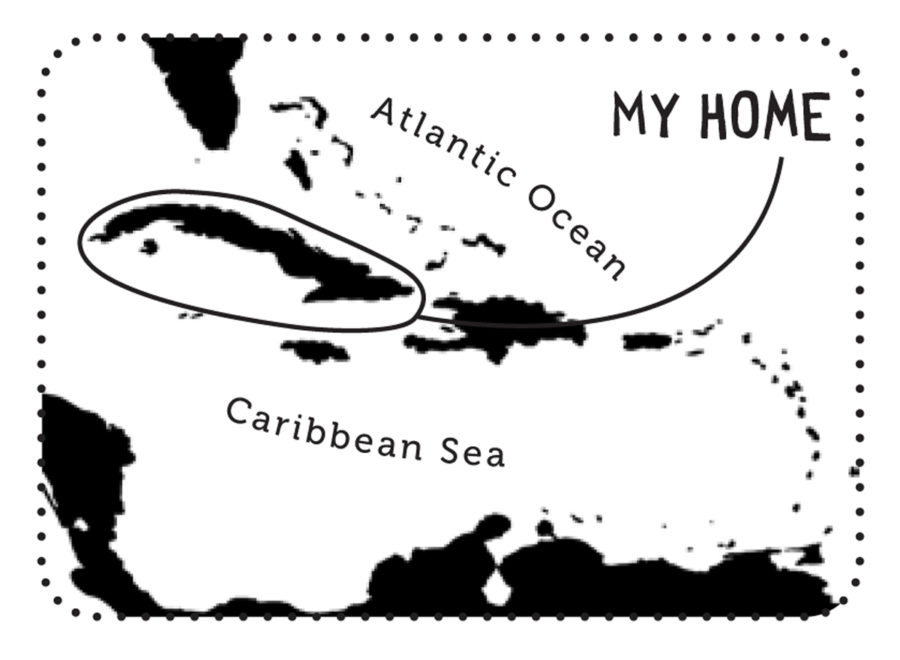

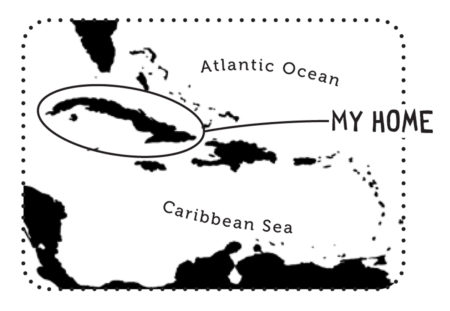

Blue-headed Quail-Doves are endemic to Cuba. They were formerly common and widespread throughout Cuba but today are rare and classified as Endangered. They are now found in only a few forested areas, including Guanahacabibes Peninsula, Zapata Swamp, and in the Pinar del Río Province. The major threats to this species are hunting and habitat destruction. Although protected, the species is still illegally trapped for its good-tasting meat. Blue-headed Quail-Doves nest on the ground or in cavities and low bushes between the months of March and June, and lay two white eggs. Their flight is clumsy, and they produce a characteristic loud noise when they are frightened, very similar to that of the European Partridge (Perdix perdix). This is probably why Spanish colonizers gave it its local name, Perdiz, which is Spanish for Partridge.

The Blue-headed Quail-Dove’s call, a series of two similar notes, whoooo-up, whoooo-up, seems like a whisper in the forest. It should remind us that the forest is the quail-dove’s only habitat and we must protect it to continue enjoying these beautiful birds—considered a jewel of the Cuban avifuana. Learn more about this species, including its range, photos, and calls here.

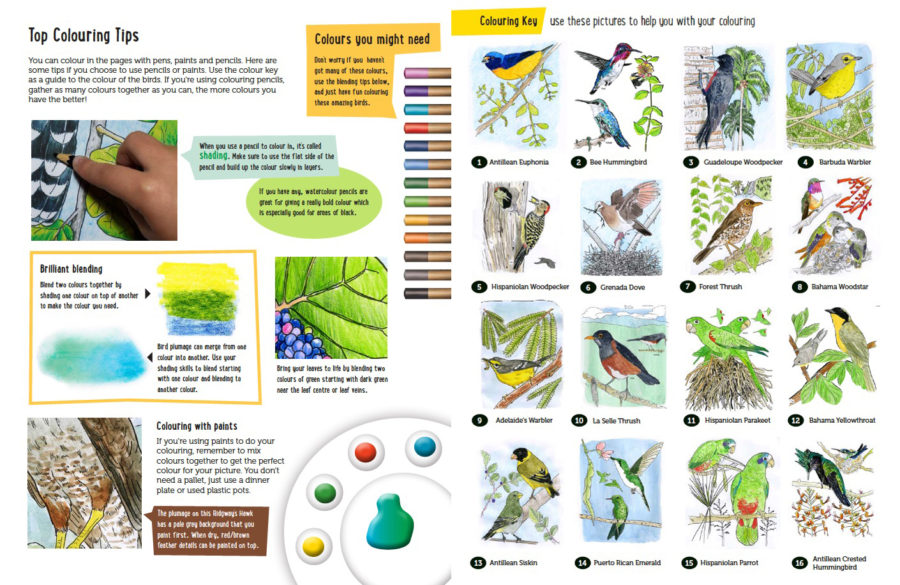

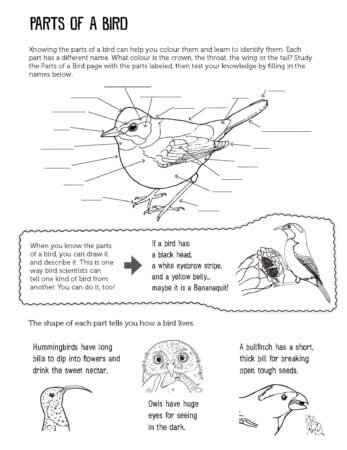

Colour in the Blue-headed Quail-Dove!

Download the page from Endemic Birds of the West Indies Colouring Book. Use the drawing above or photo below as your guide, or you can look up pictures of the bird online or in a bird field guide if you have one. Share your coloured-in page with us by posting it online and tagging us @BirdsCaribbean #CEBFfromthenest

Listen to the call of the Blue-headed Quail-Dove

The Blue-headed Quail-Dove’s call is a series of two similar notes, whoooo-up, whoooo-up, with the last syllable rising in tone and then stopping short. During the breeding season, male may call from a low perch for long periods at virtually any time of day. You can also hear the chattering call of the Cuban Tody in this recording.

Puzzle of the Day

Click on the image below to do the puzzle. You can make the puzzle as easy or as hard as you like – for example, 6, 8, or 12 pieces for young children, all the way up to 1,024 pieces for those that are up for a challenge!

Activity of the Day

FOR KIDS & ADULTS: Enjoy this short video of a male Blue-headed Quail-Dove courting a female by following her and head-bobbing. Breeding pairs are socially monogamous and defend territories during the breeding season. The nest is built of loosely placed twigs lined with freshly fallen leaves, placed either on the ground or low to it in a stump cavity, the fork of a branch among the roots of trees, and sometimes among tangled vines.

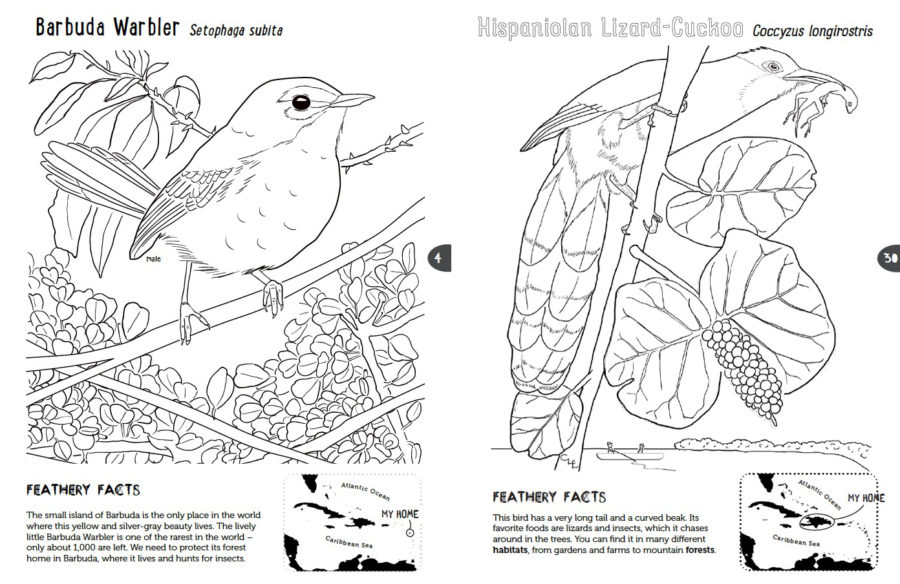

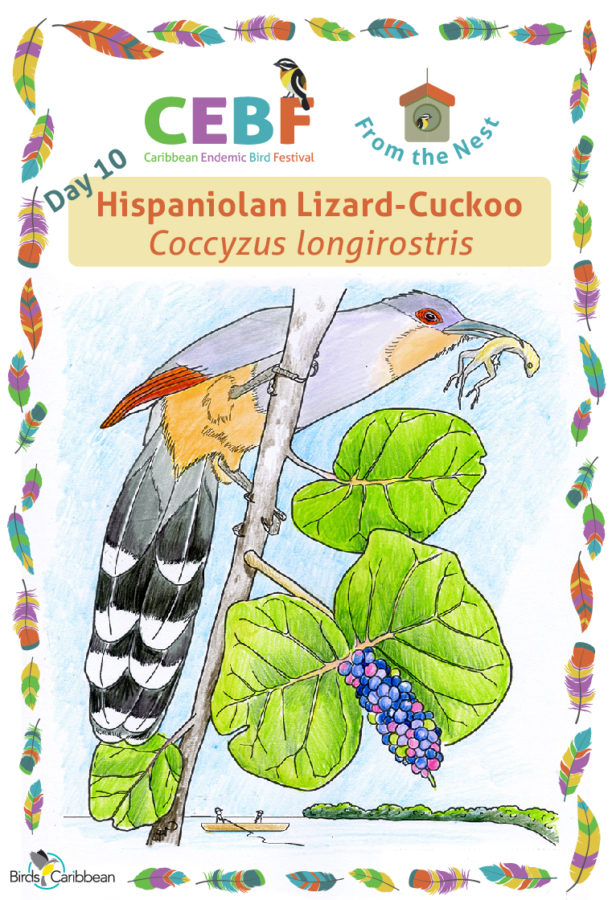

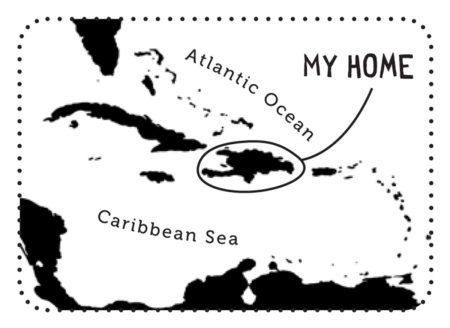

The Hispaniolan Lizard-Cuckoo is true to its common name: it is found nowhere else in the world but the island of Hispaniola, its diet includes lizards (as well as many different insects), and it belongs to the Cuculidae family. On the Dominican side of the island, this cuckoo is known as Pájaro Bobo (“Silly Bird”), while on the Haitian side it goes by the name, Tako.

The Hispaniolan Lizard-Cuckoo is true to its common name: it is found nowhere else in the world but the island of Hispaniola, its diet includes lizards (as well as many different insects), and it belongs to the Cuculidae family. On the Dominican side of the island, this cuckoo is known as Pájaro Bobo (“Silly Bird”), while on the Haitian side it goes by the name, Tako.

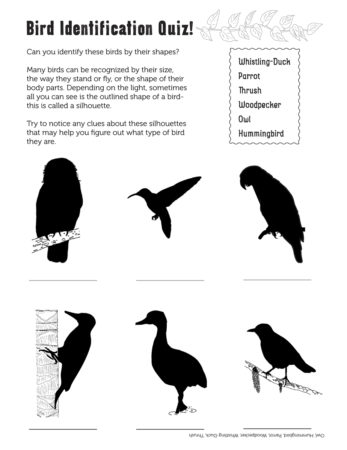

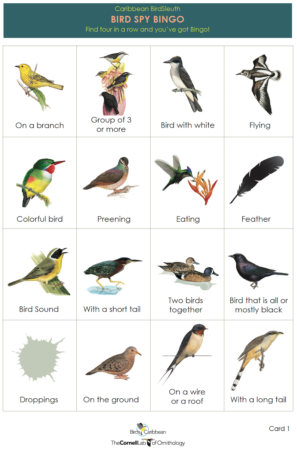

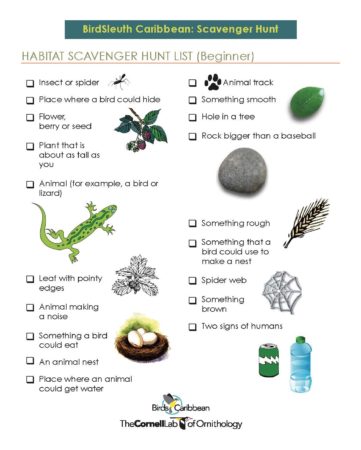

FOR KIDS: Complete our

FOR KIDS: Complete our